Unplugging in the Arctic

Rethinking Tech After a Greenland Marathon

It's almost midnight and I'm kicking back with some instant coffee – no sugar – in a B&B on the outskirts of Copenhagen, where I'm literally the only guest. This month, I hit the big 40. I spent 15 of those years hustling as an IT journalist. Tomorrow, I'll head back home to my usual grind, so I've muted all my messengers and sworn not to crash until I finish writing this piece.

Just a day ago, I got back from Greenland. I spent a week in the stunning country with virtually zero internet; cut off from work, endless pings from colleagues, and the nonstop juggling of micro-tasks.

I wasn't in Greenland for the touristy stuff. I hate tourism – it's like a plague that kills the souls of cities and countries, reducing everything to some bland, cookie-cutter experience. I used to be all about seeing the world, but after hitting 40+ countries, places started to blur together. There's the “central square with a church that some great author immortalized 400 years ago” – no different from a thousand other churches. And there's the "best pizza in town" spot where you won't find a single local, and the prices are jacked up compared to the café next door serving equally decent grub. You get the drift; no need to push it.

In Greenland, I was prepping for a marathon amidst the snow and ice, at a crisp -15°C. Over the past year, I'd knocked out a few half-marathons and the daily runs were getting stale. I craved a new challenge. Enters ‘training for a 42km race in one of the coldest spots on the planet’.

I wasn't expecting much from Greenland – I figured it's all snow and ice, and probably full of Danes. And Inuits? I thought they were just storybook characters and maybe 20 of them were left living in igloos in the middle of nowhere. I flew in to run and hadn't read up on the country, aside from some semi-adventurous tales by Danish explorer, Peter Freuchen. He’s the guy from those viral stories – the one who supposedly got trapped in an ice cave, crafted a knife out of his own poop, and dug his way out (spoiler: cool story, but not exactly true).

Harsh climates breed tough people. At the airport, this guy, around 30, was pushing two meters tall, rocking a beard, short hair, a light winter jacket, windproof pants, and a rapper-style cap with the sticker still on. His red, weather-beaten hands with half-healed scratches gave away his Greenlandic heritage, as did his awkward urge to light up right in the airport lounge. He was sneaking sips from a duty-free beer and occasionally dashed out to the freezing, windswept platform to smoke.

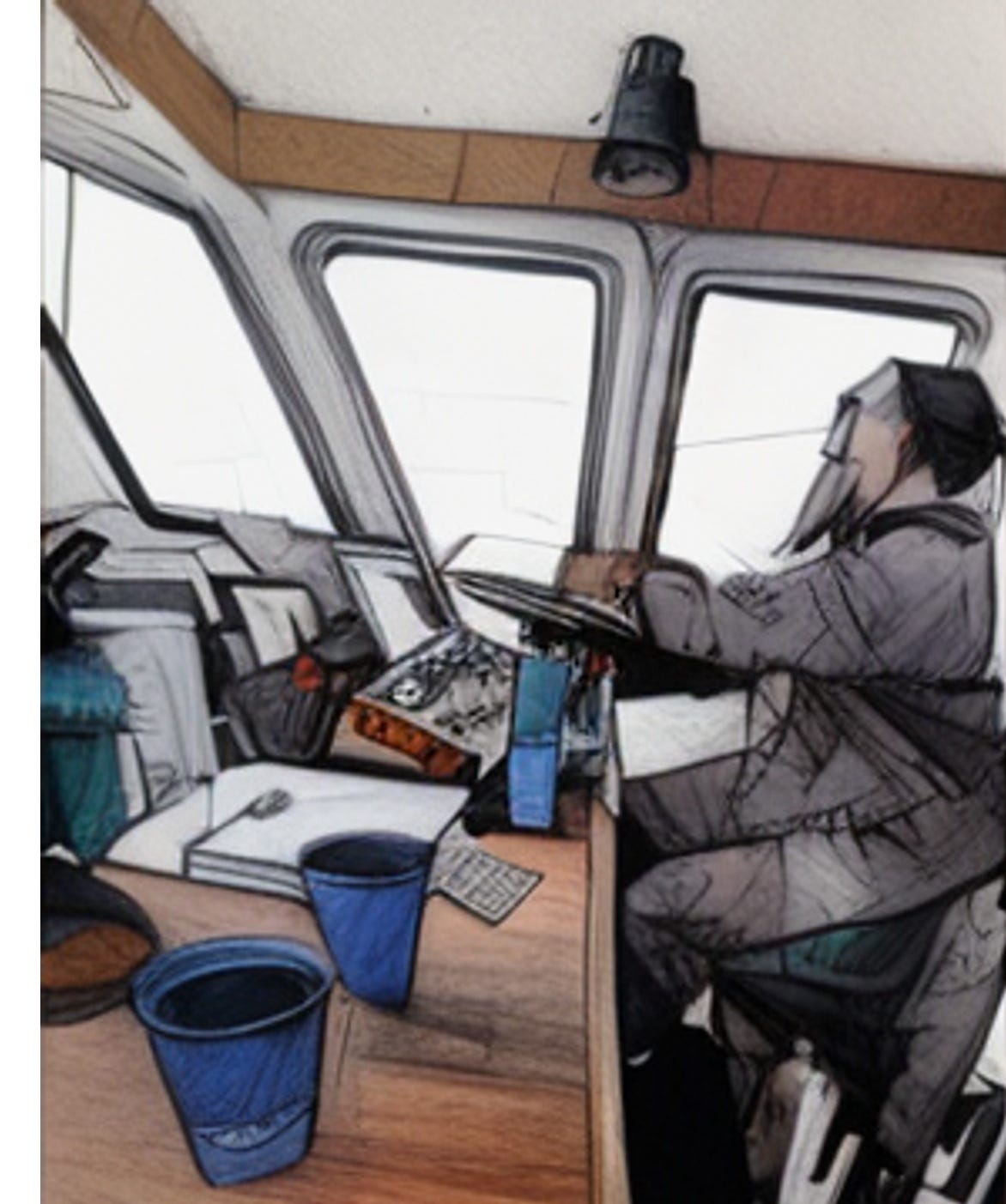

Then there was our pilot on the internal Greenland flight. A two-meter-tall jokester who, after saying "We're a free country with free people", invited a passenger to chill in the cockpit during the half-hour flight. Our group's coordinator, Bjorn, is a Dane. He's 80 and has spent 50 of those years connected to Greenland. "Why?" I asked him. "Look out the window," Bjorn replied. "There's nothing more beautiful in the world." And there's the marathon winner – a member of the local running club – who finished half an hour before everyone else, hugged his wife and kids, and didn't even look winded. No biggie – just 42 km over snow and ice at -15°C. His ancestors ran way more.

Life up north is all about simplicity. Seals and whales aren't exotic delicacies for tourists – they're just food for locals and their dogs. For centuries, Inuits didn't know about keto diets or veggies; they got all their vitamins and nutrients from meat. Take whale blubber or mattak, chew it with the skin for ages, and then swallow it whole. Whatever they caught is what they lived on, and they were glad to be alive. That's why exporting most local products to the mainland is banned. Hunting, still the main pastime for locals in winter, isn't mindless slaughter for souvenirs – it's a means to survive on an island 90% covered in ice.

Modern Greenland, however, isn't stuck in the past. Even a fishing village of 44 people has a cell tower, a government services center, and a telemedicine point. Traditional skin clothing exists, but most folks are decked out in Gore-Tex and warm, windproof jackets. Every boat has a Garmin GPS, and air travel covers pretty much the whole country. The local store isn't your typical supermarket. It's a general store with life's essentials, from apples and toothpaste to rifles. In remote settlements, these stores are subsidized by the government. Not by Europe or some foreign taxpayers, but by Greenland itself – a Danish autonomy with its own language, flag, culture, and traditions. Ask a Greenlander if they consider themselves Danish, and they'll laugh in your face.

Does this way of life make the locals unhappy? If anything, they're puzzled by the isolated life in Europe. One guy I chatted with – a Dane born in Greenland who later moved to the mainland – complained that on his birthday, he can only invite a small group of friends. Back in his hometown, people would post a visible notice in a public spot saying that Christian is celebrating his birthday on such-and-such date. That was enough for every villager to drop by with a gift and grab a drink or eat, depending on how generous the host was.

So why am I going on about Greenland? It's about a simple life filled with vivid colors and emotions – the kind of life endless streams of memes and dumb videos on social media are trying to replace. Maybe I should focus on telling stories about the positive impact of technology on our everyday lives in the near future.

Stay tuned for the next post.